Introduction

One day quite some time ago, I was walking in Amsterdam and happened to look down into one of the canals. I saw an old boat, abandoned, half-submerged, trash in the cockpit, weeds growing in the hull, her name faded by the sun and the sea. It made me melancholy to think that she was once a beautiful boat that carried her passengers to the other shore but now, with the passage of time, she will never sail again; she is abandoned and dead. I had never seen a photograph of a dead boat in Amsterdam. I felt as if I had hit upon a new image, one that avoided the tourist cliches of the bridges, the canals, the boats, the brown canal houses, the cafes, the bikes and the pretty girls. I began to search for more dead boats and found them everywhere. I have photographed them for many years and I have a large archive of images.

Over the years, I began to revisit places where I remembered that I had taken photographs of specific boats. I began to notice that some had decayed more over time, new weeds and junk filled the cockpits, some had sunk, some had disappeared entirely and new ones had taken their place. I could compare photographs and see the changes that time’s decay had wrought. The boats became a metaphor for death, time and memory. And then questions arose. Why am I so consumed with taking photographs in the first place? There is a transformation from the boat in the canal to the boat in the photograph but what does that represent? Is photography limited to only capturing fragments of the past? How does photography relate to death, time and memory? Does the photograph speak the truth or does it lie? Is it possible to create a new paradigm for photography to expand its visual language to include new developments in philosophy and technology?

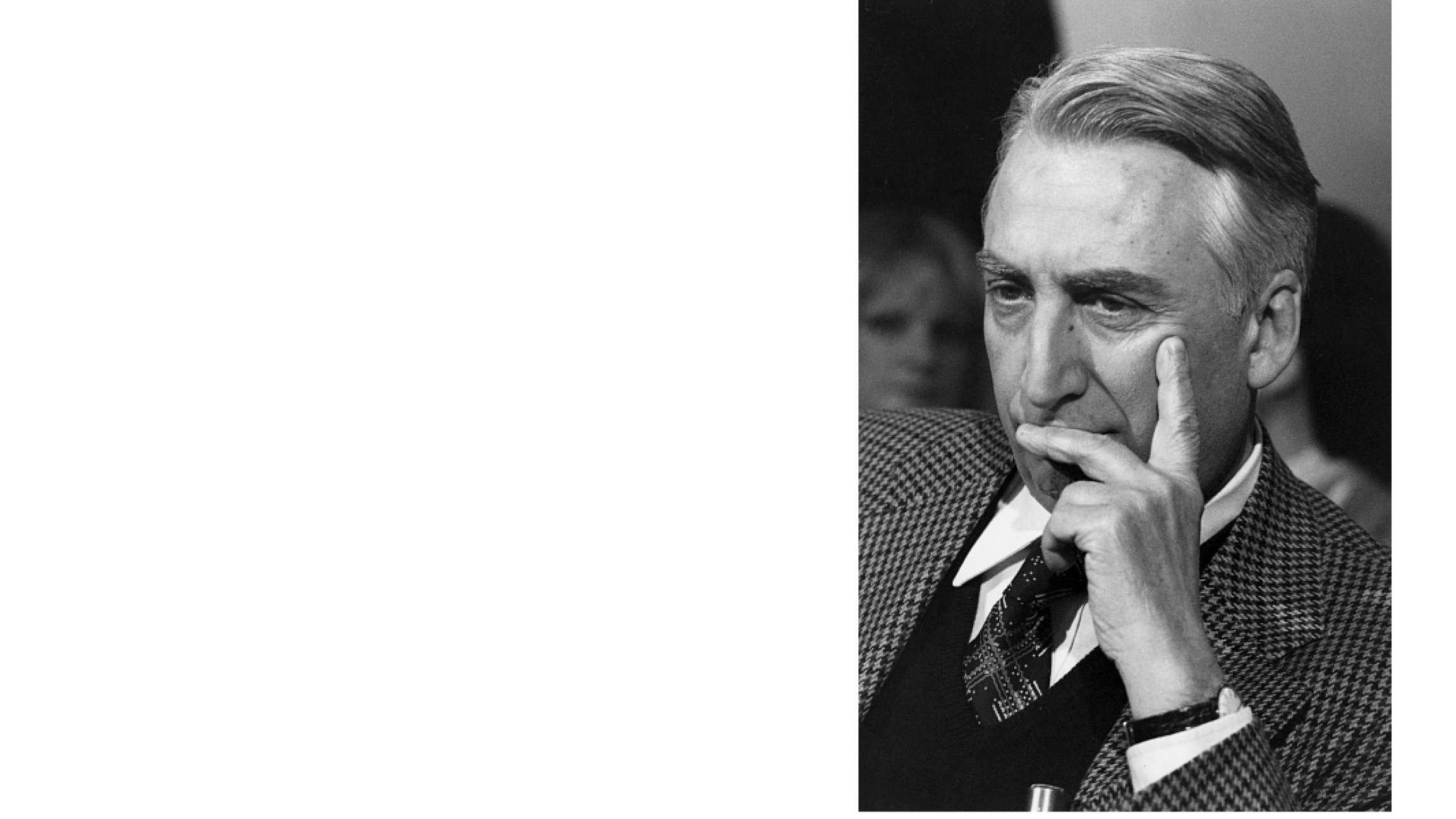

I began to research photography philosophy and discovered Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. I discovered that his writing is complex, dense, ambiguous, and sometimes contradictory. Camera Lucida incorporates many ideas from his prior works as well as oblique references to a broad range of poets, philosophers and academics from many disciplines. It is a very personal, emotional and curious work; it is concerned with ontology, discovering the eidos, the essential nature of photography, and the death and resurrection of the mother, memory and mourning.

The dead boat project became a meta-metaphor for my exploration of death, time and memory and philosophy through the lens of Camera Lucida. Could I bring something new to our understanding of Camera Lucida and the field of photography philosophy? I am not an academic but a lawyer and a photographer; perhaps my background could bring new insights.

This book is a record of my discoveries on my journey into death, time and memory and Camera Lucida; it is both a homage and a criticism. Barthes has given me the freedom to bring my subjective and personal desires, emotions and experiences into my work. I have written both from the head and the heart.

Barthes was not a photographer even though he wrote extensively on photography. Barthes was not a Buddhist even thought he wrote extensively on Buddhism. Like Barthes my mother is dead but, unlike Barthes, I have let her go. I am not searching to resurrect my mother through photography. As a photographer and a Buddhist my concerns are different. I want to break through the photographic cliche that photography is inevitably tied to the past like a fly in the amber and to discover a new paradigm for photography, one inspired by philosophy and technology. I want to understand what the photograph is actually showing us. I want to understand the genesis of my desire to take photographs. I want to understand whether photography may be a spiritual practice that can change the consciousness of the photographer and help realize Buddha mind.

Camera Lucida is Barthes’ ontological quest to find photography’s essence, its eidos. At the end of Part One he reaches a dead end. He recants Part One and writes Part Two as his palinode. He abandons his quest, and the book evolves into a novella of memory and mourning, with interstices of philosophy, over the death of his mother.

In Camera Lucida Barthes sets up many binaries: ode and palinode, studium and punctum, mad and tame, seen and unseen, form and emptiness, life and death, illusion and reality. At the end of the book, he leaves us with this unanswered question: we can subject the spectacle of photography to “to the civilized code of perfect illusions” or we can “confront in it the wakening of intractable reality.” This is the final binary and, by closing Camera Lucida with the unanswered question, Barthes abandons much of his life’s work of resisting dualistic modes of thought. He gave us a beautiful, complex and fascinating work of art but we are left many unanswered questions. This is quintessential Barthes.

Since photography has the unique function of being able to record images of everything in the universe, it follows that we must consider the qualities of the universe to discover photography’s essence. The universe is both dual and non-dual; it is both form and emptiness; it is both physical object and subtle energy; it is both reality and illusion. Although the universe appears to be dualistic in our ordinary, relative perception, the absolute truth is that it is non-dual. The universe is one, not two, and our perception of it being comprised of binaries is a relative truth; it is an illusion. To find photography’s essence we must determine whether it can capture both dual and non-dual states of being. Further, can it capture temporal states other than just the past, such as the timeless state or perhaps even the future?

Advances in science have radically changed our understanding of time, light, matter and space. These are the new elements of photography. Although we began photographing Newton’s world, we can now photograph Einstein’s world. Photography has almost limitless potential. Science has enabled it to move far beyond simply being a camera that transcribes images of the forms of the world. We have captured the emptiness of a black hole, subatomic energies and light with cameras that can exposure trillions of frames a second. Photography must capture both the dual and the non-dual world; it must capture both form and emptiness, reality and illusion, the mad and the tame, the vernacular and the sublime, life and death. After my long journey into Camera Lucida, Barthes and photography philosophy, what have I learned?

The camera creates images of death, time and memory; we see these elements in almost every photograph. There is always the passage of time, there is always memory, there is always death. Death, time and memory are interdependent; they are inseparable, they are the three sides of the triangle of existence. Time is death and memories are bound to time.

My working thesis, my ode, my Part One to Camera Lucida is that photography is comprised of three essential qualities or Platonic Forms: death, time and memory. The photograph always references death, time and memory, just as are lives are bound to death, time and memory. These Forms manifest all of the photographs in the world; there is no photograph that exists outside of these Forms.

Barthes derives the Form of photography from the famous photograph of his mother in a garden: the Winter Garden Photograph. However, he does not show us this photograph because we cannot see a Form; it is an idea, it is a perfection, it is always unseen. Death, time and memory are all embodied within the Winter Garden Photograph; it is a single image that represents the Form of all of photography. It is this Form that leads Barthes to conclude that photographers are agents of death.

Like Barthes, I discover that my ode, death, time and memory, does not answer my questions. I move from my ode to my palinode, my Part Two of Camera Lucida. My palinode is not a retraction but an expansion of my ode.

My palinode is that the Form of photography manifests both life and death. The Form of photography is death, time and memory, and life. Behind these four Forms, however, there is a higher Form, the one true Form: a single essence that manifests the multiplicity of all Forms. It is named Brahman, the absolute, the ground of all being, the source that manifests everything in the world; from the one to the many. And to put it in Zen terms, the one true Form of photography is emptiness. It has no essential quality, no inherent or intrinsic existence, no essential feature, no fixed nature. The photograph does not exist in and to itself; rather its existence is dependent upon the referent. It arises from nothingness and collapses back into nothingness. It is empty but from that emptiness it reflects all of the forms of the universe. It is like a cosmic mirror reflecting all things but containing and holding nothing. From this perspective, all of Barthes’ dualities-form and emptiness, reality and illusion, the mad and the tame, the vernacular and the sublime, life and death- collapse into unity.

It is false to see the world as comprised of the duality of life and death and then to equate photography with only one side of the duality, death. Photography is not just an expression of death. Barthes, Araki and Sontag had it wrong. It would be equally false to equate photography with the other side of the duality, life. As a photographer, I am not an agent of death. I am an agent of death and life. I photograph both life and death. I photograph both the yin and the yang and the great circle that embraces them both. Like Minor White, I use photography as a spiritual practice to awaken to non-dual awareness and to make new, creative images.

Photography may be a spiritual practice. We may use the activity of photography as an practice to be more present in the here and the now. Some photographs may be objects of meditation to help us still our minds. With still minds we may awaken to non-dual awareness which resolves our suffering and brings us peace. Even though Barthes was fluent in the language of Zen and mentioned it in many of his works, he did not see that photography may be a spiritual practice. Through practice he could have realized that the world is impermanent, accepted the loss of his mother, faced his suffering and, with the wisdom gained through practice, healed as a human being. In the end, he did not find the Form of photography, he left us with an unanswered question in a brilliant and beautiful work, mourned and died shortly after his mother.

It is time for a new definition of photography.

Photography is a dynamic system for making creative images inspired by multivalent explorations of meaning founded on modern, cosmologically valid and philosophically rigorous conceptions of time, space and light. It is a vehicle for exploring life and death, and time and memory. The photograph is an image generating system that is co-created by the photographer and the observer.

A photograph is an interpretation, a designation, a performance, a narrative, an exploration, a meta-question. It is no longer just a two-dimensional image showing us that objects have “existed” in the past. It may now be expressed as a hologram, as a sculpture, as a projection, as a mixed media installation. It may be made without a camera or a photographer. It may represent the non-dual world and the timeless state of expanded consciousness. It may be an abstract image with no predicate based on the observable world. Photography is no longer limited to representing a rigid and false duality of present and past, of dynamic movement and stasis, of mourning and loss, of decaying and dying as time flows from present to past. It is no longer limited by Barthes’ duality of being either an illusion or reality. It is both and neither; its true essence is emptiness which enables it to reflect all forms of the world.

My journey into Camera Lucida has ended in San Diego where my spiritual life began. The circle is complete. I write these last words on Moonlight Beach as the sun sets over the Pacific Ocean. With a silent mind, I contemplate the sun and the sea, the wind and the waves, the cliffs and the palm trees, the sail boats on the horizon. I witness a perfect world that is beyond death, time and memory and that can never be captured by a camera. A seagull passes across the sun. Light, shadow, form. Light. As it was written in the Upanishads, Tat Tvam Asi, You Are That. Such is the way of photography. Not two. One.

How To Read This Book

Intertext

The inspiration for the text of this book relies upon the notion of the intertext. Intertextuality depends upon the figures of the web and the weave; it is like a written garment woven from textual threads that have been already written and read by others before the author. It is like a music composition of figures, metaphors and thought-words. Graham Allen explains:

The act of reading, theorists claim, plunges us into a network of textual relations. To interpret a text, to discover its meaning, or meanings, is to trace those rela- tions. Reading thus becomes a process of moving between texts. Meaning becomes something which exists between a text and all the other texts to which it refers and relates, moving out from the independent text into a network of textual relations. The text becomes the intertext.

Graham Allen, Intertextuality

Barthes understood this when he wrote Camera Lucida; it is profoundly an intertextual work. Barthes views the intertext as a “multidimensional space”:

We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God) but a multidimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture … the writer can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior, never original. His only power is to mix writings, to counter the ones with the others, in such a way as never to rest on any one of them. Did he wish to express himself, he ought at least to know that the inner ‘thing’ he thinks to ‘translate’ is only a ready-formed dictionary, its words only explainable through other words, and so on indefinitely.

Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author

In addition to the photographs displayed and discussed in the text, Barthes mentions many philosophers, writers, poets and films. Here is a sampling: Lacan, Watts, Atget, Mapplethorpe, Sartre, Klein, Niepce, Baudelaire, Freud, Proust, Warhol, Kertesz, Kafka, Proust, Schumann, Ariadne, Nietzsche, Blanchot, Antonioni’s Blow-Up and Fellini’s Casanova. These references are woven into Barthes’ own web of text and images. Even though the Camera Lucida is about the ontology of the image, the book is a personal and a remarkably human work. Barthes considers his childhood, the death of his mother, his suffering and his alienation as he writes Camera Lucida.

My study of Camera Lucida led me to many of Barthes’ earlier works such as A Lover’s Discourse, Empire of the Signs, Mythologies, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, Mourning Diary and The Neutral. To explicate Camera Lucida and to support my theories, I read Aristotle, Plato, Buddha, Bergson, Blanchot, Deleuze, Sartre, Joyce, Heidegger, Rilke, Marker, Godard and Krishnamurti. To support my theories I studied photographers such as Nobuyoshi Araki, Wolfgang Tillmans, Gregory Crewdson, the Starnes Twins, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Minor White.

As I wrote this book I began to see deep associations among my Barthian studies, my photography, my literary interests and my personal experiences. A few intertextual examples: Barthes, Buddhism, Joyce, Amsterdam, San Diego, Nepal, Sisyphus, Proteus, the Sirens, Dedalus, the labyrinth, the boats, the mother, the sea, silence, cunning and exile, death, time and memory.

I have freely woven all of these connections together to produce this work. Barthes gave me permission and I follow in his footsteps.

Camera Lucida Book Design

Camera Lucida’s is designed as a book with Two Parts; each part has 24 Chapters. Part One is the ode and Part Two is its palinode. Part One is generally concerned with Barthes’ attempt to find the eidos or Form of photography and Part Two is more concerned with the death and the resurrection of his mother, his mourning and suffering. Much of Barthes’ prior thought is condensed and interwoven throughout the book. Many philosophers and scholars are obliquely discussed and quoted in the book. As I noted above, the book contains a selection of photographs that are discussed to varying degrees. Importantly, the first image in the book is Polaroid by Daniel Boudinet but it is not mentioned in the text. Barthes extensively discusses the Winter Garden Photograph but he does not include the photograph in the book.

Because Camera Lucida is composed of two parts, it is dualistic in structure. The book design supports the many binary figures that Barthes sets up in the work.

However, my book is composed of three parts. I go beyond Barthes’ dualism and assert that the answer to the question of photography’s essence lies in non-duality.

Parts One (Eidos) and Part Two (Camera Obscura) represent dualism and Part Three (Satori) represents non-dualism.

Camera Lucida is an unusual work because it is personal, emotional, intellectual, and analytical all at the same time. It is a blend of philosophy, photography, death and mourning. The writers and artists it references are astonishing. Barthes gave me the freedom to read and explore widely and to include stories from my life and my personal literary interests in my work. The result is that many intertextual connections between Camera Lucida and my work arose. Intertextual reading encourages us to resist a passive reading of texts from cover to cover. As Allen observes: There is never a single or correct way to read a text, since every reader brings with him or her different expectations, interests, viewpoints and prior reading experiences. Each reader of this study is encouraged to read it in whatever order best suits his or her purpose. By the same token, you should feel free to read my book in any order that seems most relevant and interesting to you. Follow the threads and see where they lead!

Although my original concept was to embody this work as a book, I decided to publish it as a website. This would allow the book to grow organically because I can include blog posts to add new material or to refine and expand upon the points made in the book. It allows me to continually modify the text that I have already written. A website allows me to link text to images in an interactive way and to include a database of images that support the book. Finally, an interactive and living website seemed more in the spirt of the intertext than a static book.

Navigation

Part One, Two and Three are top level links on the Home page. The Master Index page contains links to the main subheadings of the three Parts. The Photography page contains photographs that support the text. The Blog contains posts on current topics of photography and modifications of the text of the book.

Copyright

This book is being published under the Creative Commons License BY-NC. This license allows re-users to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in this book in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

If you wish to obtain a PDF version of the entire book, please contact me and I will be happy to send one to you.